THE NEED FOR MINIMUM LIGHT

Numerous disasters have proved that many people can remain calm for several days in total darkness. But some occupants of a shelter full of fearful people probably would go to pieces if they could see nothing and could not get out. It is easy to imagine the impact of a few hysterical people on the other occupants of a pitch-dark shelter. Under wartime conditions, even a faint light that shows only the shapes of nearby people and things can make the difference between an endurable situation and a black ordeal.

Figure 11.1 shows what members of the Utah family saw in their shelter on the third night of occupancy. All of the family's flashlights and other electric lights had been used until the batteries were almost exhausted. They had no candles at home and failed to bring the cooking oil, glass jar, and cotton string included in the Evacuation Checklist. These materials would have enabled them to make an expedient lamp and to keep a small light burning continuously for weeks, if necessary.

At 2 AM on the third night, the inky blackness caused the mother, a stable woman who had never feared the dark, to experience her first claustrophobia. In a controlled but tense voice she suddenly awoke everyone by stating: "I have to get out of here. I can't orient myself." Fortunately for the shelter- occupancy experiment, when she reached the entry trench she overcame her fears and lay down to sleep on the floor near the entrance.

Conclusion: In a crisis, it is especially bad not to be able to see at all.

Fig. 11.1. Night scene in a trench shelter without light.

ELECTRIC LIGHTS

Even in communities outside areas of blast, fire, or fallout, electric lights dependent on the public power system probably would fail. Electromagnetic pulse effects produced by the nuclear explosions, plus the destruction of power stations and transmission lines, would knock out most public power.

No emergency lights are included in the supplies stocked in official shelters. The flashlights and candles that some people would bring to shelters probably would be insufficient to provide minimum light for more than a very few days.

A low-amperage light bulb used with a large dry cell battery or a car battery is an excellent source of low-level continuous light. One of the small 12-volt bulbs in the instrument panels of cars with 12-volt batteries will give enough light for 10 to 15 nights,

Book Page: 101

without discharging a car battery so much that it cannot be used to start a car.

Making an efficient battery-powered lighting system for your shelter is work best done before a crisis arises. During a crisis you should give higher priority to many other needs.

Things to remember about using small bulbs with big batteries:

o Always use a bulb of the same voltage as the battery.

o Use a small, high-resistance wire, such as bell wire, with a car battery.

o Connect the battery after the rest of the improvised light circuit has been completed.

o Use reflective material such as aluminum foil, mirrors, or white boards to concentrate a weak light where it is needed.

o If preparations are made before a crisis, small 12-volt bulbs (0.1 to 0.25 amps) with sockets and wire can be bought at a radio parts store. Electric test clips for connecting thin wire to a car battery can be purchased at an auto parts store.

CANDLES AND COMMERCIAL LAMPS

Persons going to a shelter should take all their candles with them, along with plenty of matches in a waterproof container such as a Mason jar. Fully occupied shelters can become so humid that matches not kept in moisture-proof containers cannot be lighted after a single day.

Lighted candles and other fires should be placed near the shelter opening through which air is leaving the shelter, to avoid buildup of slight amounts of carbon monoxide and other headache-causing gases. If the shelter is completely closed for a time for any reason, such as to keep out smoke from a burning house nearby, all candles and other fires in the shelter should be extinguished.

Gasoline and kerosene lamps should not be taken inside a shelter. They produce gases that can cause headaches or even death. If gasoline or kerosene lamps are knocked over, as by blast winds that would rush into shelters over extensive areas, the results would be disastrous.

SAFE EXPEDIENT LAMPS FOR SHELTERS

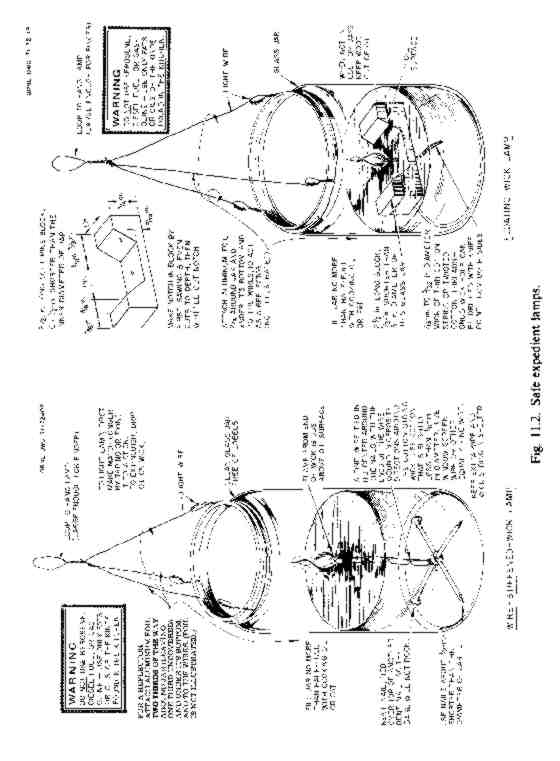

The simple expedient lamps described below are the results of Oak Ridge National Laboratory experiments which started with oil lamps of the kinds used by Eskimos and the ancient Greeks. Our objective was to develop safe, dependable, long- lasting shelter lights that can be made quickly, using only common household materials. Numerous field tests have proved that average Americans can build good lamps by following the instructions given below (Fig. 11.2).

These expedient lamps have the following advantages:

o They are safe. Even if a burning lamp is knocked over onto a dry paper, the flame is so small that it will be extinguished if the lamp fuel being burned is a cooking oil or fat commonly used in the kitchen, and if the lamp wick is not much larger than 1/16 inch in diameter.

o Since the flame is inside ajar, it is not likely to set fire to a careless person's clothing or to be blown out by a breeze.

o With the smallest practical wick and flame, a lamp burns only about 1 ounce of edible oil or fat in eight hours.

o Even with a flame smaller than that of a birthday candle, there is enough light for reading. To read easily by such a small flame, attach aluminum foil to three sides and the bottom of the lamp, and suspend it between you and your book, just high enough not to block your vision. (During the long, anxious days and nights spent waiting for fallout to decay, shelter occupants will appreciate having someone read aloud to them.)

o A lamp with aluminum foil attached is an excellent trap for mosquitoes and other insects that can cause problems in an unscreened shelter. They are attracted to the glittering light and fall into the oil.

o Two of these lamps can be made in less than an hour, once the materials have been assembled, so there is no reason to wait until a crisis arises to make them. Oil exposed to the air deteriorates, so it is best not to store lamps filled with oil or to keep oil-soaked wicks for months.

Book Page: 102

Fig. 11.2. Safe Expedient Lamps

Book Page: 103